Picturing Life through Pichwai

Remember how it feels to unwrap a present? With a similar feeling of sweet anticipation, the visitors awaited to witness what would unfold. Meanwhile, as a pair of eyes examined a wondrous artwork of Shri Nath Ji, another appreciatively gazed at Bani Thani. An air of curiosity hung about the air. At the Pichwai booth, the group of college youngsters awaited the unveiling of an artwork, wondering what secrets lay hidden within its depths.

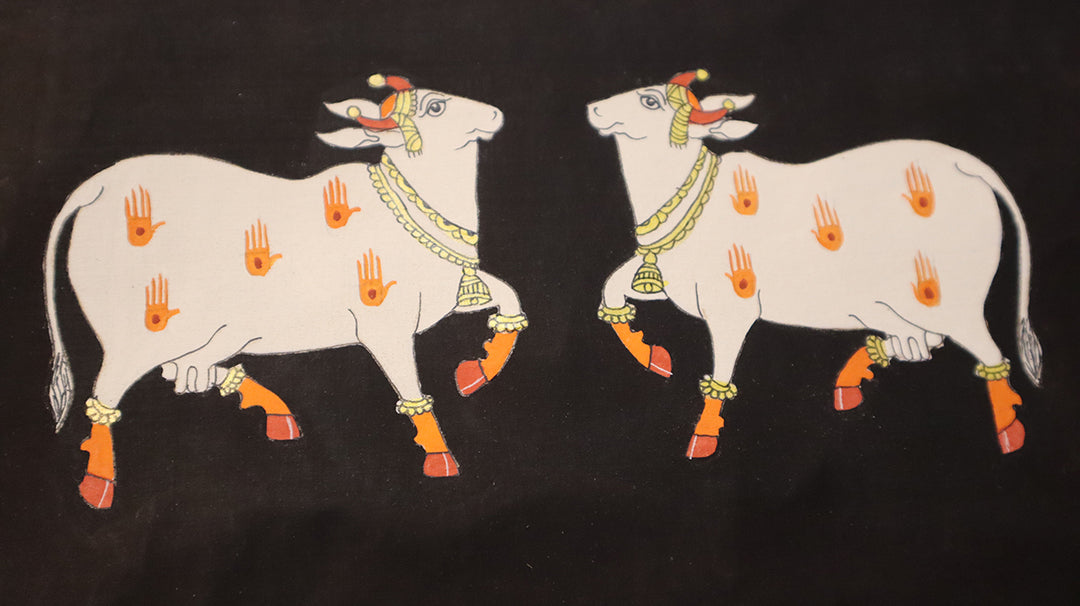

As Mr Nand Kishore Sharma unraveled the canvas, beautiful Pichwai cows sprawled across the dark backdrop.

“How many cows are there?”, one asked.

“A total of 108,” he replied, his tone measured and precise.

“Any specific reason for that?” Another inquired following suit, curiosity piqued by the deliberate choice of number.

“ An entire tale I’d say. Up for a storytelling session?”

“Absolutely!”, the group claimed in excited unison, ready to be swept away by the rich narrative about to be unfolded before them.

The 108 Cows Shri Yantra Pichwai

In the universal scheme of existence, from the vast expanse of the cosmos down to the minutiae of everyday life, there exists a profound interconnectedness that weaves through the fabric of reality. Particles, energy, atoms, galaxies - each influence the other in the symphony of creation. When this cosmic ballet transcends human expression, we often shape its essence in the form of art. Across cultures and epochs, art mirrors the cosmic order at its core- transforming the ineffable into tangible forms of expression. Be it a stroke of the brush, a note of a melody, or a word penned, each reflects the eternal dance of creation and destruction. In a way, we as humans tend to turn the mundane into the sublime, don’t we?

Among the diverse array of art forms, one serving as a conduit between the mortal, the divine, and the cosmic order is the traditional art of Pichwai. It is believed to have originated in the sacred town of Nathdwara which is also the home to the renowned Shrinathji temple. Since childhood, we have grown up listening to the tales of Lord Krishna. Pichwai reveres his seven-year-old ‘Baal Swarup’, his infant incarnation, better known as - Shrinathji.

Shrinathji Pichwai

The art captures the divine presence but you might wonder how figures of bovines across canvas symbolize a microcosm of the cosmic order. The painting is called The 108 Cows Shri Yantra Pichwai. Shri Yantra or the ‘sacred instrument’ is a mystical diagram holding profound significance in the Shri Vidya tradition of Hindu worship, embodying the union of divine masculine and feminine energy. How so? It consists of nine triangles, four pointing upwards embodying Shiva, the masculine energy, and five pointing downwards, symbolizing Shakti, the female energy. Together, the triangles form a web symbolic of the entire cosmos originating from the center, i.e. the Bindu. Wherever three lines meet on the Shri Yantra, it creates a point of convergence known as Marma, totaling up to fifty-four such intersections. Each of these intersections embodies the complementary forces of Shiva and Shakti. With 108 (54x2) such intersections in total, the Shri Yantra depicts the union of opposites within the cosmic fabric.

When this particular painting was made, the Shri Yantra grid was considered to determine aspects of the length and width of the painting. The catch- where the 108 marma points lie on the grid are the places where the cows are painted. Also known as Govinda the cowherd, Lord Krishna spent his childhood and youth tending to cows and calves in Vrindavan. Hence, a Pichwai featuring bovines pays homage to his adoration towards his cows while signifying an abundant and prosperous life when one devotes his heart in worship to the almighty.

Mr Nand Kishore Sharma, Pichwai Artisan

But how is the precise ratio of 108 woven into the very fabric of our being? Is it possible to solve the mysteries of creation through mere numbers? Can a numerical connect the ancient to the present, the physical and the metaphysical? In the annals of our heritage, the significance of 108 echoes loudly. When our forebears, the ancient scientists of yore peered through the veil of time and space, they discerned the hand of mathematical precision weaving a narrative of divine harmony and cosmic resonance. The yogis, the mystic, -and even the physicist Galileo Galili believed that a secret lay in the mysteries of numbers and mathematical calculations.

The number of beads in malas used for japa (repetition of meditative mantras), the cycles of Pranayama, the twelve postures of sun salutations completed in nine rounds, the energy lines or nadiis converging to form the heart, the types of definements in Buddhist tenets, names of each deity in Hinduism, the steps and columns of Angkor vat temple, the natural division of a circle in geometry, the Upanishads, the diameter of the monument Stonehenge in feet, all have one aspect in common- the number 108. Indian cosmology emphasizes this number as the basis of all creations. The number "1" stands for divine consciousness, the number "0" for emptiness and vanity due to the transient nature of existence, and the number "8" for the infinite possibilities of creation. It also exists in concepts ranging from science and spirituality to space and mathematics.

108 times the diameter of the moon will give you the distance between the Earth and the moon. Similarly, 108 times the diameter of the sun shall give the distance between the Earth and the Sun. In fact, the sun's diameter is 108 times that of the earth’s. Go back to Vedic times and the number preaches spiritual completion, the wholeness of existence. The Vedic sages credited with inventing the integer version of the numeral system coined 108- the Harshad number. Divisible by the sum of its digits, it means a ‘source of joy’ in Sanskrit. Isn't it fascinating how what we initially viewed as theological and cultural elements happen to permeate nearly every aspect of life?

Pichwai artisans with students learning about the art tradition

The eyes of the students shone with the wonderment of having known a mystery they weren't aware of! In the farther corner of the Pichwai booth, sat Mr Kalyanmal Sahu adjusting the folds of the hung paintings. “How about you now have a chat with Maestro Sahu, my ally and senior in this art patronage!” And once again, the enthusiastic flock grouped for another storytelling session.

The art that has you enthralled finds its humble origins in Shrinathji Haveli, Udaipur, a revered religious site where the idol of Shrinathji is venerated. In Sanskrit, “pich” refers to back, and “wai” means to hang, hence signifying the tradition of hanging these paintings behind idols. The art began in the form of a service called Chitraseva, wherein the chitrakars (artists) depicted various Leelas (divine acts) of the deity capturing the essence of the eight darshans (views) of god throughout the day through their art. Each darshan corresponds to a specific time and occasion, and Pichwais are crafted accordingly, portraying the divine forms and significant events associated with them.

Mr. Kalyanmal Sahu, Pichwai Artisan

Carrying on the tradition, I proudly call myself a chitrakar devoted to this craft. Going beyond its aesthetic appeal, different scenes of Shrinath ji’s life are illustrated on Pichwais adorning the wall behind the idol, celebrating the triumph of good over evil. Pichwai of every festival- Holi, Teej, Raksha Bandhan, and Deepawali carries a distinct essence of its own. To accommodate the needs of modern homes and spaces, the size of the paintings has however been reduced according to the changing times and preferences. As beautiful as the paintings look, the preparation for making them is as intense.

Upon a wooden platform, a cloth sheet is pasted which becomes the base of our painting. Then we begin the process by preparing the canvas, which is treated with a layer of starch called lei made from ararot (arrowroot), sabudana (sago) and maida (wheat flour). Once the surface becomes stiff, it is rubbed with stones to achieve a smooth texture and finish. Given the elaborate and detail-oriented nature of the art, the color composition is kept subtle. With the same meticulousness are the natural colors prepared. The process begins with grinding mitti (soil) colors, filtering them in water multiple times, and adding gum arabic to the mixture to achieve a smooth consistency. Ingredients such as zinc oxide, khadiya, orange sindoor, and indigo are incorporated. The mixture is then further processed through a sieving process known as "Kharail mein Ghutai" to refine it upon which colors are finally used. Such is the ultimate composition of the painting, that the deity acts is emphasized as the central figure and is surrounded by miscellaneous elements like gwal baal (shepherds), gopiyaan (milkmaids), and mor (peacock), directing the viewer's focus towards the divine presence.

Like any other traditional art, I feel Pichwai too needs to be preserved and propagated given its rich heritage and cultural significance. Besides the craft bazaars, what are the possibilities that you’d encounter upon learning about folk art? It’s essential that its knowledge is incorporated into formal education and public awareness programs to ensure its continuity and appreciation for future generations. After all, art is for all, right? It shouldn't be just relegated to the realm of artisans and craft enthusiasts.

This timeless tradition finds its soul in its ability to connect individuals with their spiritual roots and strength in its beauty. What could be more beautiful than that?